Memento mori is Latin for “Remember death.” The phrase is believed to originate from an ancient Roman tradition in which a servant would be tasked with standing behind a victorious general as he paraded through town. As the general basked in the glory of the cheering crowds, the servant would whisper in the general’s ear: “Respice post te! Hominem te esse memento! Memento mori!” = “Look behind you! Remember that you are but a man! Remember that you will die!”

We don’t like to think too much about death. It’s a bit too depressing and morbid for our think-positive sensibilities. Our culture is devoted to perpetuating the lie that you can stay young forever and your life will go on and on.

But for men living in antiquity all the way up until the beginning of the 20th century, rather than being a downer, death was seen as a motivator to live a good, meaningful, and virtuous life. To help men remember death, artists created paintings, sculptures, and mosaics depicting skulls, skeletons, and other symbols of death. Churches would display memento mori art to compel viewers to meditate on death, reflect on their lives, and re-dedicate themselves to preparing to meet God. Devout Christians would often ask that their tomb or grave marker have some sort of skeleton motif on it to remind their visiting family members to get right with God before they too bit the dust.

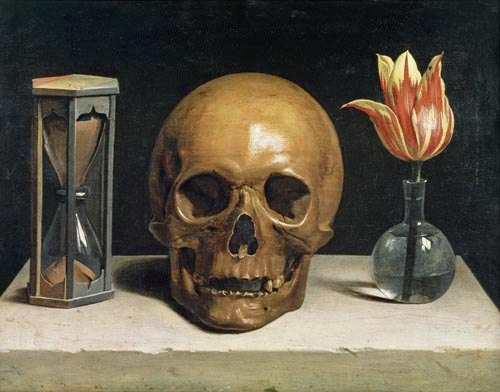

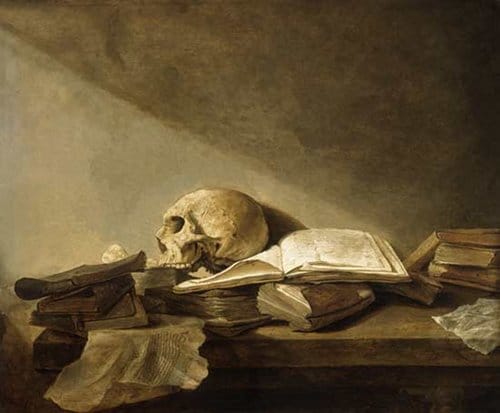

Below is one of the memento mori’s art called vanitas.

Vanitas Vanitatum Omnia Vanitas

Still Life with a Skull by Philippe de Champaigne, 1671. The three essentials of existence: life, death, and time.

The famous passage from chapter 1 of Ecclesiastes on the fleeting and impermanent nature of our mortal life is cited as the inspiration for this morbid art.

2 Vanity of vanities, saith the Preacher, vanity of vanities; all is vanity.

3 What profit hath a man of all his labour which he taketh under the sun?

4 One generation passeth away, and another generation cometh: but the earth abideth for ever.

5 The sun also ariseth, and the sun goeth down, and hasteth to his place where he arose.

6 The wind goeth toward the south, and turneth about unto the north; it whirleth about continually, and the wind returneth again according to his circuits.

7 All the rivers run into the sea; yet the sea is not full; unto the place from whence the rivers come, thither they return again.

8 All things are full of labour; man cannot utter it: the eye is not satisfied with seeing, nor the ear filled with hearing.

9 The thing that hath been, it is that which shall be; and that which is done is that which shall be done: and there is no new thing under the sun.

10 Is there anything whereof it may be said, See, this is new? it hath been already of old time, which was before us.

11 There is no remembrance of former things; neither shall there be any remembrance of things that are to come with those that shall come after.

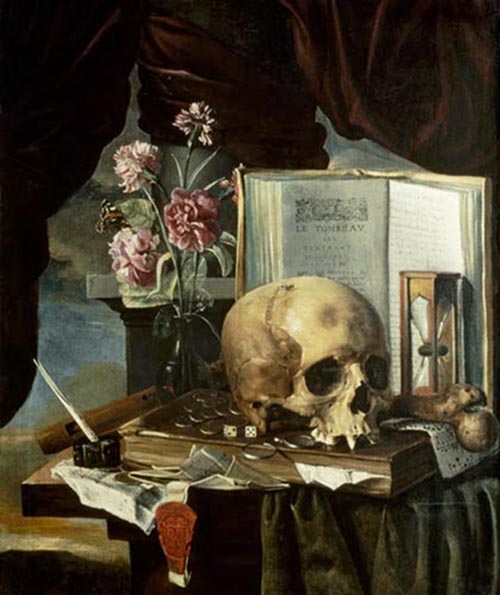

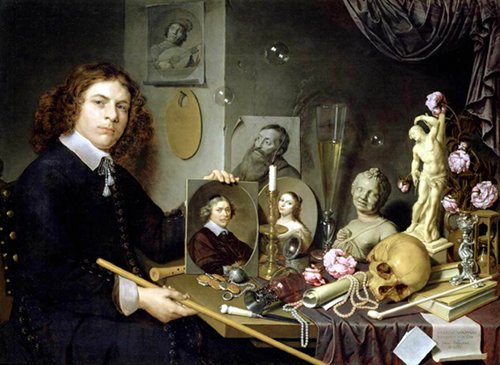

In vanitas art, the certainty of death and our mortality are still the main themes, but there’s an added emphasis on the fleetingness and insignificance of earthly glory and pleasures. Common symbols in vanitas art include the skull (representing the certainty of death); bubbles (representing the brevity and fragility of life and earthly glory); smoke, hourglasses, and watches (every minute that passes brings you closer to death); rotting fruit and flowers (representing the fragility and decay of earthly things); musical instruments and music sheets (representing the ephemeral nature of life); torn or loose books (representing earthly knowledge); and dice and playing cards (representing the role that chance and fortune play in life).

The purpose of vanitas art is moral instruction. It’s to remind the viewer that life is precious, so they better not waste it on frivolous and meaningless things.

In Meditations Marcus Aurelius wrote “You could leave life right now. Let that determine what you do and say and think.” That is a personal reminder to continue living a life of virtue NOW, and not to wait.

Track your life in weeks and contemplate the Tail End.

Since reading The Tail End by Tim Urban, I’ve thought about this message nearly every day. It’s as equally morbid/daunting as the Memento Mori coin can be.

Stop what you’re doing and go read the full posts Your Life in Weeks and The Tail End. Seriously. Do it now.

Welcome back.

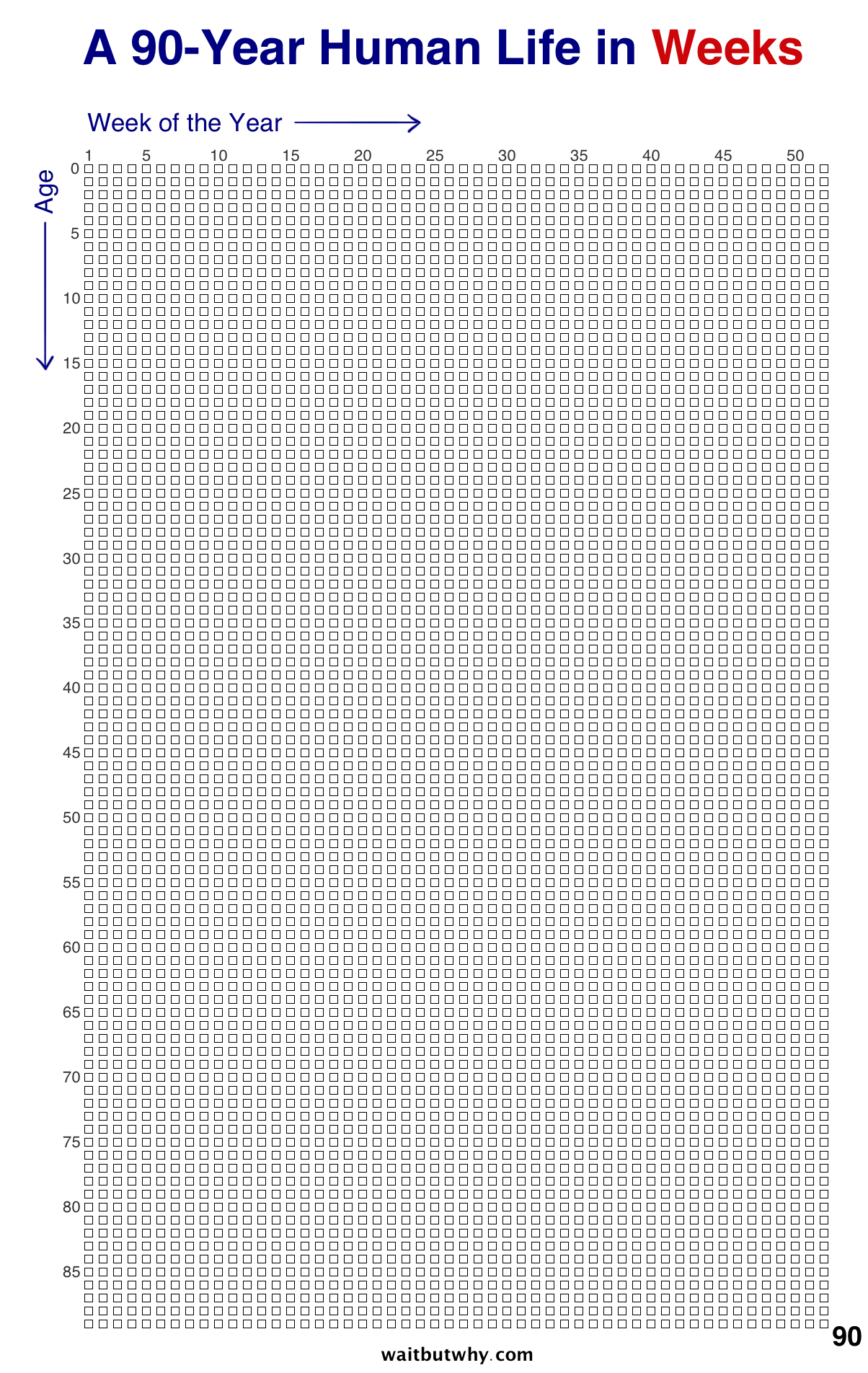

Your Life in Weeks led to The Tail End. What you see above is a life lived to 90 years with each box representing one week. 52 columns. 90 rows. Most people don’t live to 90, so this is the exception rather than the rule, but a good illustration nonetheless. Your life fits on one sheet of paper here. At the end of each week. Check off another box. Did you use that box well? You don’t get it back.

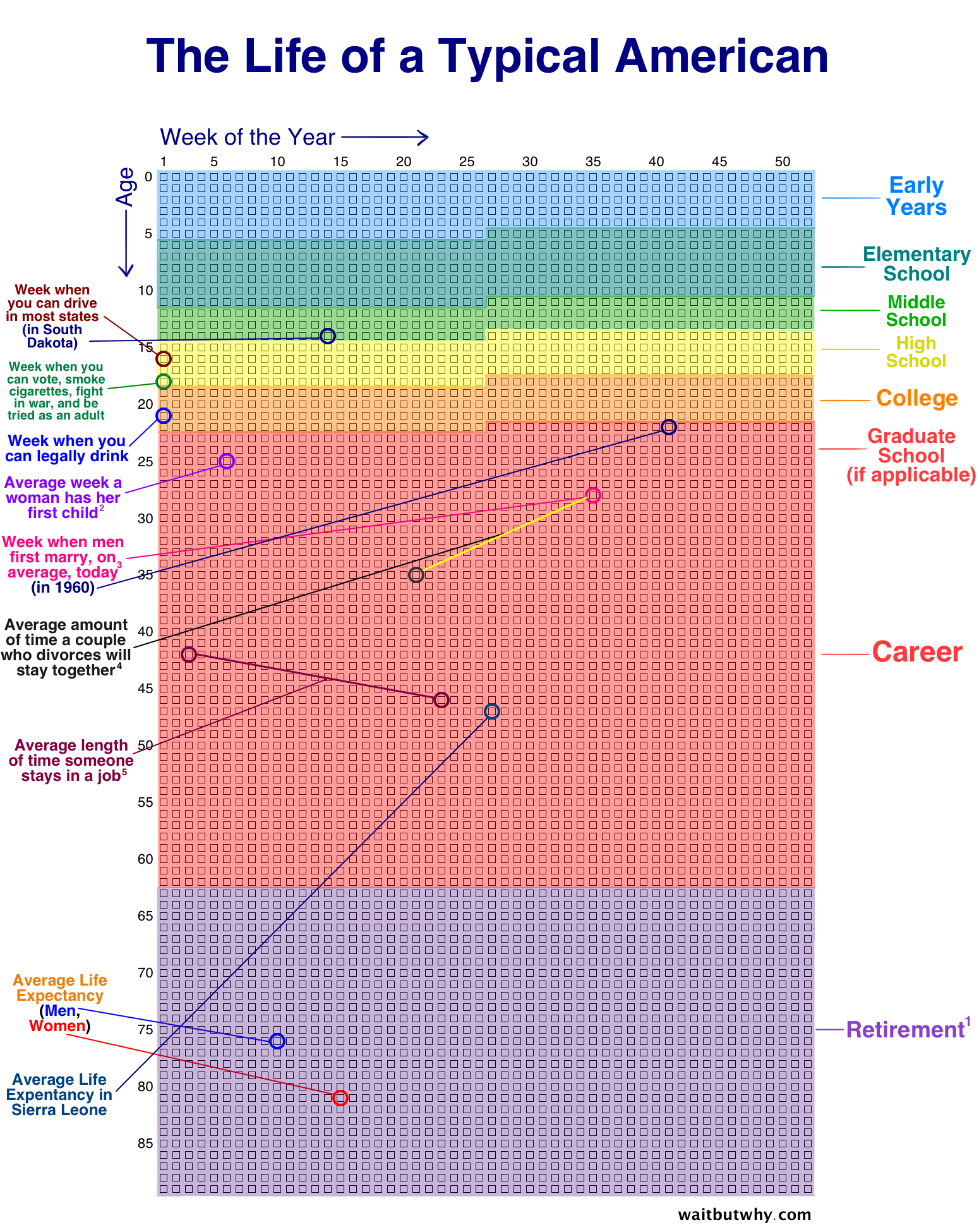

Taking an example from Tim’s Wait But Why,Below is a more powerful visualization.

Stop what you’re doing and go read the full posts Your Life in Weeks and The Tail End. Seriously. Do it now.

Welcome back.

Your Life in Weeks led to The Tail End. What you see above is a life lived to 90 years with each box representing one week. 52 columns. 90 rows. Most people don’t live to 90, so this is the exception rather than the rule, but a good illustration nonetheless. Your life fits on one sheet of paper here. At the end of each week. Check off another box. Did you use that box well? You don’t get it back.

It is staggering to look at this. If you have read these posts, GO READ THEM ONCE MORE.

Tim takes it to the next level in The Tail End:

“Instead of measuring your life in units of time, you can measure it in activities or events.” — Tim Urban

If you see your best friend from high school every other year, how many times do you have left in your life to see them? How often do you see your parents? Once or twice a year? How many days left do you get with them, if you’re lucky? Tim swings an existential, emotional hammer down with this thought about relationships and the people that matter most in life.

“I’ve been thinking about my parents, who are in their mid-60s. During my first 18 years, I spent some time with my parents during at least 90% of my days. But since heading off to college and then later moving out of Boston, I’ve probably seen them an average of only five times a year each, for an average of maybe two days each time. 10 days a year. About 3% of the days I spent with them each year of my childhood.

Being in their mid-60s, let’s continue to be super optimistic and say I’m one of the incredibly lucky people to have both parents alive into my 60s. That would give us about 30 more years of coexistence. If the ten days a year thing holds, that’s 300 days left to hang with mom and dad. Less time than I spent with them in any one of my 18 childhood years.

When you look at that reality, you realize that despite not being at the end of your life, you may very well be nearing the end of your time with some of the most important people in your life.

It turns out that when I graduated from high school, I had already used up 93% of my in-person parent time. I’m now enjoying the last 5% of that time. We’re in the tail end.” — Tim Urban

The weight of this is almost too much to bear at times; however, you can start focusing on being grateful and embracing this reality.

In 1973, cultural anthropologist Ernest Becker published The Denial of Death, a profound book that claimed that people are too terrified of death to face it. Because that fear is so deeply rooted and so much more powerful than the immediate fears of one’s daily life, the near-universal response has been to deny that it’s coming at all. This seems to be confirmed in our current culture, especially collegiate culture, as there is a flippant air of invincibility that only gives a second thought to our mortality for the briefest of seasons when tragedy strikes.

In the book, Becker asserts, “To live fully is to live with an awareness of the rumble of terror that underlies everything.” Are we not all longing to be aware of what is true rather than escaping it with a mind-numbing drug or hobby? Are we really so naive that we will, like a child playing hide-and-seek, place our hands over our eyes and convince ourselves that death is no longer there? If we want to live, let’s call a spade a spade. Death is both inevitable and terrifying, and denying it will accomplish nothing but emotional shallowness.

Read the entire entire book here.

Memento mori, friends.

Vanitas Still Life by Simon Renard de Saint-André, middle of the 17th century.

Vanitas Still Life by Jan Davidsz de Heem, 17th century

Vanitas Still Life by Simon Renard de Saint-André, middle of the 17th century. Notice the hourglass, pair of dice, and sheet of music.

Self-Portrait with Vanitas Symbols by David Bailly, 1651. Notice the bubbles.