“A human being should be able to change a diaper, plan an invasion, butcher a hog, conn a ship, design a building, write a sonnet, balance accounts, build a wall, set a bone, comfort the dying, take orders, give orders, cooperate, act alone, solve equations, analyze a new problem, pitch manure, program a computer, cook a tasty meal, fight efficiently, die gallantly. Specialization is for insects.”

-Robert A. Heinlein

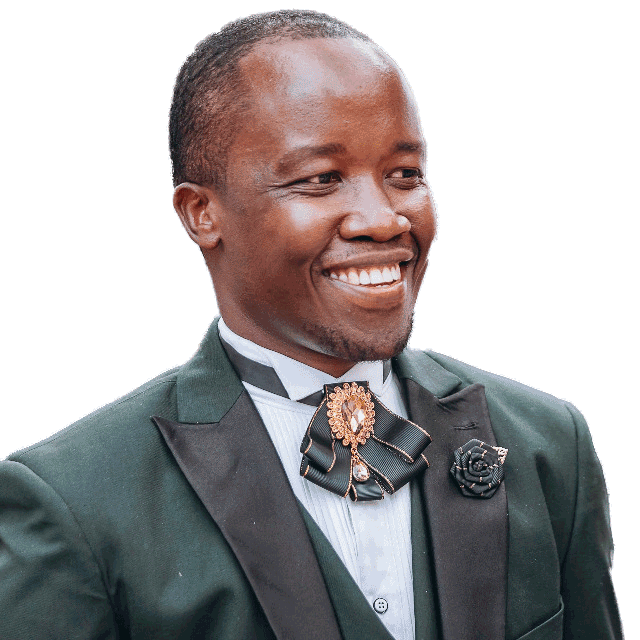

A while ago a friend of mine called me just to catch up with what I was up-to with my life. He knows I am an electrical engineer and thus he expected the updates on my career to be purely on electrical engineering. Well I am interested in a variety of fields including education, mentoring, farming, programming, ICT, Writing books and electrical engineering. When he got to know about my progress on some of these fields he sounded flabbergasted. He couldn’t understand why I had spent five years in campus studying engineering and here I was, “A jack of all trades” in his eyes. Is there anything wrong with being a Jack of all trades at these modern, technology driven times? Is the age of the likes of Benjamin Franklin over?

Well I came across a quite well thought rebuttal to the much parlayed idea “Jack of all Trades – Master of None”. Tim Ferriss, A life hacker puts this matter to rest in his blog post ““The Top 5 Reasons to Be a Jack of All Trades”.

He writes,

“Jack of all trades, master of none” is an artificial pairing.

It is entirely possible to be a jack of all trades, master of many. How? Specialists overestimate the time needed to “master” a skill and confuse “master” with “perfect”…

Generalists recognize that the 80/20 principle applies to skills: 20% of a language’s vocabulary will enable you to communicate and understand at least 80%, 20% of a dance like tango (lead and footwork) separates the novice from the pro, 20% of the moves in a sport account for 80% of the scoring, etc. Is this settling for mediocre?

Not at all. Generalists take the condensed study up to, but not beyond, the point of rapidly diminishing returns. There is perhaps a 5% comprehension difference between the focused generalist who studies Japanese systematically for 2 years vs. the specialist who studies Japanese for 10 with the lack of urgency typical of those who claim that something “takes a lifetime to learn.” Hogwash. Based on my experience and research, it is possible to become world-class in almost any skill within one year.

In a world of dogmatic specialists, it’s the generalist who ends up running the show.

Was Steve Jobs a better programmer than top coders at Apple? No, but he had a broad range of skills and saw the unseen interconnectedness. As technology becomes a commodity with the democratization of information, it’s the big-picture generalists who will predict, innovate, and rise to power fastest. There is a reason military “generals” are called such.

Boredom is failure.

In a first-world economy where we have the physical necessities covered with even low-class income, Maslow’s hierarchy of needs drives us to need more for any measure of comparative “success.” Lack of intellectual stimulation, not superlative material wealth, is what drives us to depression and emotional bankruptcy. Generalizing and experimenting prevents this, while over-specialization guarantees it.

Diversity of intellectual playgrounds breeds confidence instead of fear of the unknown.

It also breeds empathy with the broadest range of human conditions and appreciation of the broadest range of human accomplishments. The alternative is the defensive xenophobia and smugness uniquely common to those whose identities are defined by their job title or single skill, which they pursue out of obligation and not enjoyment.

It’s more fun, in the most serious existential sense.

The jack of all trades maximizes his number of peak experiences in life and learns to enjoy the pursuit of excellence unrelated to material gain, all while finding the few things he is truly uniquely suited to dominate.

The specialist who imprisons himself in self-inflicted one-dimensionality — pursuing and impossible perfection — spends decades stagnant or making imperceptible incremental improvements while the curious generalist consistently measures improvement in quantum leaps. It is only the latter who enjoys the process of pursuing excellence.

A nice and helpful read ?